Why exercise can’t make up for a bad diet- How to break a weight loss plateau

Why Exercise Can’t Make Up for a Bad Diet? Eat less, exercise more. You’ve probably heard that’s the secret to weight loss. So, it makes sense that if you want to lose weight quickly, or if you’ve hit a weight-loss plateau, you need to really ramp up the exercise, right?

Unfortunately, many people experience frustration with this approach. Why aren’t they successful? Research suggests that weight loss can be more complex than a simple “calories in/calories out” formula. In fact, our hormones play a larger role in regulating our metabolism than many people realize. As a result, maintaining a diet that encourages hormonal balance is often more effective than hours of exercise.

Do the math to calculate your calorie burn

Consider a woman training for a 10-K race. She runs from half an hour to an hour every day. With all of that exercise, she figures she should be losing weight and should be able to treat herself every so often. However, she’s plagued by some remaining pounds that she just can’t shake.

What’s happening? Let’s take a look at the math. As a 140-pound woman, she burns about 300 calories in a 30-minute run. And that’s fantastic! In addition to the calorie loss, she experiences cardio health, mood elevation, and countless other benefits (including a sense of accomplishment!) from her runs.

However, those 300 calories are a lot easier to consume than they are to burn. Simply put, she can consume 300 calories by eating a small bagel or sipping on a sweet coffee drink.

In fact, studies have shown that exercising often leads to an increase in food consumption. Some of this effect may be due to our hormones’ impacts on appetite, and some of it simply might be because we tend to tell ourselves (often subconsciously) that we deserve more food after a workout.

The Science Of Exercise And Appetite

Interestingly, one study found that a modest amount of exercise (about 30 minutes a day) is more effective for losing body fat than longer periods of working out. One reason for this might be that our everyday movement (the things we do in a normal that are not related to formal exercise) may decrease if we’re tired from a long workout. As well, the hormones that stimulate our appetite may increase when our bodies are overstressed.

What does this mean for your weight-loss efforts? All told, scientists have concluded that diet is more effective than exercise for weight loss. However, the best approach combines the two. That’s because it’s important not to dismiss exercise’s role. Working out can improve your metabolism, particularly if you add strength training to your routine. And, of course, – exercise offers countless other benefits, from better skin to improved digestion to deeper sleep. It’s an important part of a healthy, balanced life.

The Most Effective Formula For Weight Loss

So, what is the ideal weight loss formula? The best approach is one that reflects your unique health profile. Your age, gender, overall health and lifestyle all impact your metabolism. That’s why it’s important to work with your healthcare practitioner to develop a strategy that works for you and to make sure there isn’t something else going on that’s sabotaging your ability to reach your weight loss goals.

Breaking A weight Loss Plateau – Tips for Success

A few simple changes can help you make the most of the “diet” part of the equation so that you experience the weight-loss benefits of both diet and exercise.

Experiment with intermittent fasting to find a fasting schedule that works for you.

Intermittent fasting involves integrating scheduled periods of abstaining from food. There are many different approaches you could try. To name a few popular examples, some people eat regular meals five days a week and fast for the other two. And many people follow an “8-16” schedule, in which they eat for eight hours a day (for example, 10:00 to 6:00), then fast for 16 hours.

Studies have found that the effectiveness of these periods of fasting goes beyond the missed calories because of the effect on your hormones – for example, periods of not eating can help keep insulin levels in check. When your food is digested in your gut, carbs are converted to sugar and used for energy.

But excess sugar is stored as fat, with the help of insulin. If your insulin levels drop, fat cells can release this stored sugar. In addition, fasting can elevate your levels of human growth hormone (HGH) which can lead to muscle growth and fat loss.

-

Keep a food diary.

One strategy that has been proven effective for weight loss is to carefully monitor what you’re eating in a food diary. Making this a habit can help prevent the tendency many of us have to overcompensate for an exercise session or grab a quick snack without realizing the extra intake and its effect.

-

Focus on natural, nutrient-dense whole foods.

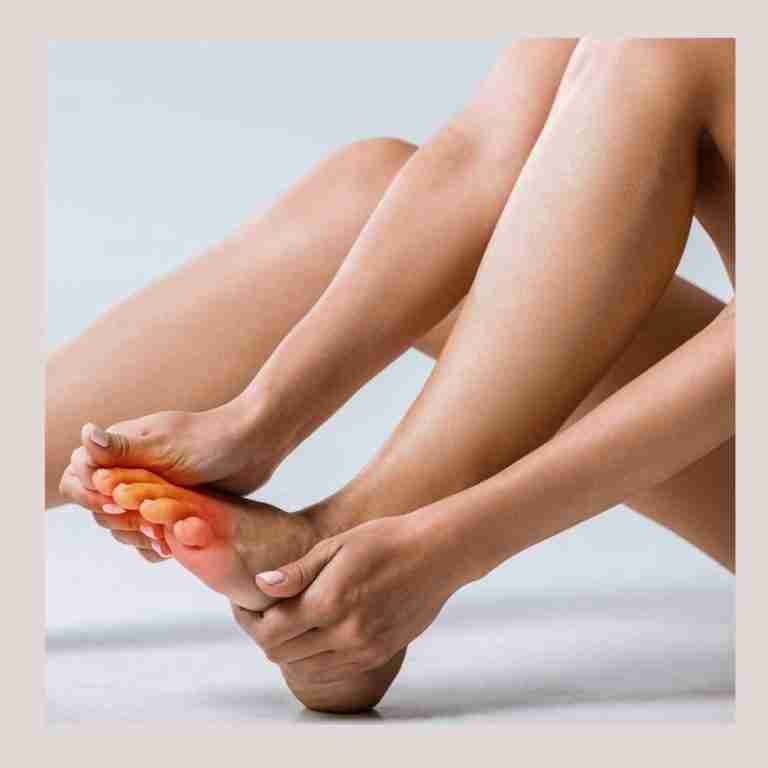

When you want to get the most nutrient value from the foods you eat, “clean” eating is the best approach. Often when people hit plateaus in their weight-loss efforts, hormone imbalances are to blame. And that means that no amount of extra exercise will help break the plateau. Nutrient-dense foods are full of vitamins and minerals that can help restore hormonal balance. So try cutting out processed foods, refined sugar, and alcohol in favor of whole foods.

Understanding how your unique body is working involves testing, not just guessing, and this holds true for weight loss. Maybe it’s a hormonal imbalance or food sensitivities that are impacting your body’s ability to metabolize food properly and stay slim.

As always, a personalized approach will be the most effective. If you’ve hit a weight-loss plateau, or if you’re wondering how to achieve the right balance between diet and exercise, I am happy to help!

Read more about the https://galpal.net/9-everyday-ways-to-practice-self-care-for-better-health/nine everyday ways to practice self care for better health, which includes drinking enough water.

Resources:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1550413118302535

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25323965

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4227972/

https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/93/2/427/4597724

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3771367/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21832897?dopt=Abstract

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3268700/